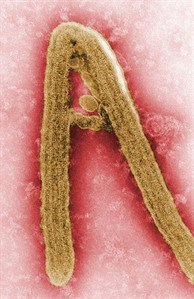

This colorized negative stained transmission electron micrograph (TEM), captured by F.A. Murphy in 1968, depicts a Marburg virus virion, which had been grown in an environment of tissue culture cells. An experimental drug for the Marburg virus appears to be able to beat back the often fatal infection even when given several days after exposure, a new study suggests. THE CANADIAN PRESS/HO - CDC, F.A. Murphy

Republished August 20, 2014 - 1:19 PM

Original Publication Date August 20, 2014 - 11:10 AM

TORONTO - An experimental drug for the Marburg virus appears to be able to beat back the often fatal infection even when given several days after exposure, a new study in primates suggests.

The drug, called TKM-Marburg, is made by Tekmira Pharmaceuticals of Burnaby, B.C., and uses the same mode of action as the company's experimental Ebola therapeutic, TKM-Ebola.

Marburg and Ebola are different — though related — members of the filovirus family. The fact that the Marburg drug appears to work when given late provides additional hope the same may be true about TKM-Ebola, some experts suggest. But the company itself was cautious on that front.

"The work we have conducted in TKM-Marburg cannot be said to be predictive of how TKM-Ebola might work in humans. However, the studies validate Tekmira's technology," it said via email Wednesday.

The Marburg drug saved four of four rhesus monkeys which were given the compound three days after they were infected with a massive dose of the virus. When they were treated, the monkeys already had viremia — virus in the blood.

The senior researcher on the project, Tom Geisbert, suggested this evidence of efficacy once infection has taken root means the drug may be useful in outbreak settings, where people typically only seek care once they develop symptoms of the disease.

"This is one of the first studies to show that there's real world application to these tools that we've developed in the lab," said Geisbert, a professor of microbiology and immunology at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston and a longtime filovirus researcher.

The drug is what is called a small interfering RNA or siRNA. It works by blocking the Ebola virus's ability to replicate itself.

The study was published in the journal Science Translational Medicine. The research was funded by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and some of the authors, including Geisbert, have an intellectual property claim on the use of siRNA technology for filovirus infection.

Tekmira hasn't yet tested this drug in people. But it has done a preliminary human safety study with its TKM-Ebola drug. That work was put on hold in early July when the U.S. Food and Drug Administration raised concerns about side-effects seen at high doses. The hold was partially lifted recently to allow compassionate use of the drug in the outbreak currently afflicting several West African countries.

The company said earlier it would be willing to allow the Ebola product to be used in the outbreak. But last week it said regulatory issues still have to be worked out, adding there is no guarantee that will happen.

The company has not said how much of the TKM-Ebola product it has. But Geisbert said it would probably be easier and quicker to scale up production of the siRNA drugs than the other experimental drug used recently, ZMapp. It is a combination of three monoclonal antibodies that target specific parts of the Ebola virus.

To date most of the studies of Ebola and Marburg drugs have only tested the effectiveness of the various compounds at early points after exposure to the virus, in the range of an hour or a day.

Something that works in that kind of time frame might be useful for an accidental infection in a laboratory or when health-care workers treating infected patients have a risky exposure. But most cases in an outbreak only come to light when a person becomes sick and that generally doesn't happen within a 72-hour window. The incubation period for Ebola and Marburg — the time from exposure to evident illness — is between two and 21 days.

Dr. Heinz Feldmann — a sometimes collaborator of Geisbert's who was not involved in this work — called the study "a milestone."

"They finally have something that works still at the time you have clinical symptoms. And if you translate that back into human disease, normally you don't get a human into the public health system before they show clinical symptoms,'' said Feldmann, who heads the virology lab at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases's Rocky Mountain Laboratories in Hamilton, Mont.

Feldmann developed an experimental Ebola vaccine while at the Public Health Agency of Canada's National Microbiology Laboratory in Winnipeg; this is the vaccine that Canada is donating to the containment effort in West Africa.

The vaccine has been shown to save Ebola-infected primates if given shortly after infection. But it has never been shown to save a primate when given as late as Geisbert gave the Marburg drug in this study, said Feldmann in an interview from Monrovia, Liberia, where he is working on the Ebola outbreak response.

The Marburg drug targets a strain of that virus called Angola; it was responsible for a 2005 Marburg outbreak in Angola that killed roughly 90 per cent of known cases. But Geisbert said the drug appears to work against other strains of Marburg as well. "It's cross protective against all the Marburgs that we know of at this time."

Geisbert said the very high doses of virus used in this study speed up the disease course in the primates. So Day 3 post infection might actually be more like Day 6 or 7 for a person.

He said work will be done to see if the drug remains effective if given later still.

While Geisbert was hopeful that this research shows TKM-Marburg could be used in a normal treatment setting, Dr. Daniel Bausch wasn't convinced.

Bausch, an associate professor at Tulane School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine in New Orleans, La., said that while the monkeys in the study had viremia, the drug was given before they had visible symptoms of illness. He suggested humans at this stage of infection probably wouldn't come forward for treatment.

"I don't want to say it's not an important and good study. It is a development that is of note and anything that has efficacy we're happy to put into the mix of possibilities of things to work up and work through," said Bausch, who will be working at the World Health Organization over the next month or so on deploying experimental therapies in this outbreak.

"I think this definitely is a drug worth exploring and this paper represents an advancement worth noting, but it's not a eureka moment of 'Here's the cure for all our ills.'"

Follow @HelenBranswell on Twitter.

News from © The Canadian Press, 2014