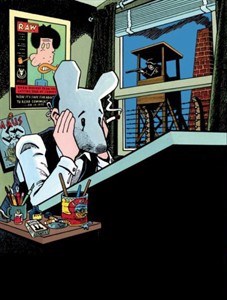

Art Spiegelman's "Self-Portrait with Maus Mask," is shown in a handout photo. Spiegelman's "CO-MIX: A Retrospective" exhibition opens at the Art Gallery of Ontario on Saturday. THE CANADIAN PRESS/HO-Art Gallery of Ontario

Republished December 18, 2014 - 5:20 PM

Original Publication Date December 18, 2014 - 1:30 PM

TORONTO - Comics master Art Spiegelman says he's rejected multiple offers to make a film adaptation out of his Pulitzer Prize-winning, Holocaust-themed graphic novel "Maus," and he'll continue to do so.

"I wouldn't like to see it," he said in an interview at the Art Gallery of Ontario, which opens his "CO-MIX: A Retrospective" exhibition on Saturday.

"I've told my kids this as well, so that they'll remember after I'm just a GIF."

Spiegelman was referring to a digital format which compresses video into short, looping clips. It's a tool the 66-year-old likely won't be using in his work anytime soon.

The "explosion" happening in the digital world of Web comics is one that has left Spiegelman "almost bewildered," he admitted.

"It's a flood that I can't possibly keep up with," said the Swedish-born, New York-raised artist. "I'm kind of stuck in my century of really liking paper, and so I'm looking at how a future might exist that allows the kinds of things I can identify with to continue."

As the AGO exhibition shows, incorporating a hand-made element into a mass-printed magazine has been a passion of Spiegelman's since he began his career as a freelance artist at the Topps Chewing Gum company and then in San Francisco's underground "comix" movement.

Back then, "comics had a real renaissance," he said, and he felt that in order for them to survive "they'd have to become art or disappear." He also liked that comics were "pages of increment" with "a visual unit of information that allows you to see lots of stuff simultaneously and then move through it at your own pace."

"Comics are important because they mimic the way the mind works," said Spiegelman. "We think in iconic images like emoticons, we think in little visual things that aren't holograms or photographs that are simplified brain drawing cartoons. We think in little bursts of language, not in long-winded paragraphs."

Spiegelman brought that outlook to major projects including the avant-garde magazine RAW, which he co-founded with wife Francoise Mouly in the '80s, when he also became popular with the card series Garbage Pail Kids. The magazine recruited up-and-coming cartoonists and started publishing serialized chapters of "Maus."

Based on Spiegelman's father's experiences as a Polish Jew in death camps during the Second World War, the first six chapters of "Maus" were eventually published in book form in 1986. A second volume with the last five chapters in the story, which depicts Jews as mice and Nazis as cats, was published in 1991. A year later the story won the Pulitzer.

"If I had been born, like, 10 years or 15 years later, I don't know that I would have done a Holocaust-related book," said Spiegelman. "When this project started, it was for a three-page comic strip in 1972. When I did that strip, I don't even think that the Holocaust was a common phrase. It was referred to as 'genocide' or 'Auschwitz,' but it wasn't branded the same way it became branded. It was well before there would be the best Holocaust movie of the year at the Oscars.

"It was just things that I knew because I grew up with it and it was a story that wasn't known at the time, so it wasn't like trying to find a variant on a story."

Spiegelman said while researching the first volume of "Maus," he was able to read "everything written in English — academic journals and elsewhere — about the Holocaust in six weeks."

"Now that would take several lifetimes," he added, "and the more you read the more there would be, and I don't know if I would have entered into it under those circumstances. That wouldn't have been necessarily a subject for me, because I'm kind of occluded, I don't realize what's going on around me until well after it's happened."

Looking back on such work, especially at his retrospective exhibition, is something Spiegelman admits he grapples with.

"I'm repulsed by and don't look at it, and then I keep thinking back to earlier things I've done as models for what I want to do next and that might fit into what I want to do next," he said, sitting in the gallery that includes a facsimile of the first volume of "Maus" and the original manuscript of the second volume.

"So it's a complicated relationship. I basically can't see the work on this wall. I just can't look at it. I don't know what it is."

Spiegelman added he's "very grateful" and in support of the exhibit, which generally runs in chronological order and also includes photographs of Spiegelman and family members as well as sketches and self-portraits. It ends with his work in the 2000s, including his 9-11 piece "In the Shadow of No Towers" and his art in The New Yorker.

Overall, the exhibit that's already been in France, Germany and New York reflects his entire body of work with "Maus" as the focal point, which pleases him.

"This shows how 'Maus' was actually a consciously chosen style, not the way I draw," said Spiegelman, "because there are so many different ways I make marks now, and one can see what they were before and what they've been since."

He added: "Every once in a while, there's a piece that I'll catch out of the corner of my eye and go, 'That's better than I thought.'"

News from © The Canadian Press, 2014